| Author |

Topic: Harmonized notes in Hawaiian music |

Peter Krebs

From:

Portland, Oregon, USA

|

Posted 5 Jul 2024 3:39 pm

Posted 5 Jul 2024 3:39 pm |

|

| Howdy folks. Having trouble wrapping my theory brain around harmonizing below the melody. I’ve been learning a lot of Hawaiian material lately and my double-stop harmonized melodies typically have the melody note on top and a harmonized note either a minor third or a major third below (on the adjacent lower-pitched string). Sounds right, just don’t know what to call it or how to explain it to myself/others. I’m used to thinking/singing a third or fifth above the melody - that makes sense. Just not the reverse. Any help appreciated!! Thanks! |

|

|

|

Peter Krebs

From:

Portland, Oregon, USA

|

Posted 5 Jul 2024 6:16 pm

Posted 5 Jul 2024 6:16 pm |

|

| When I say minor third or major third below the melody, I’m just referring to the distance of the interval, not a chord tone. |

|

|

|

Dave Magram

From:

San Jose, California, USA

|

Posted 8 Jul 2024 2:27 pm

Posted 8 Jul 2024 2:27 pm |

|

Peter,

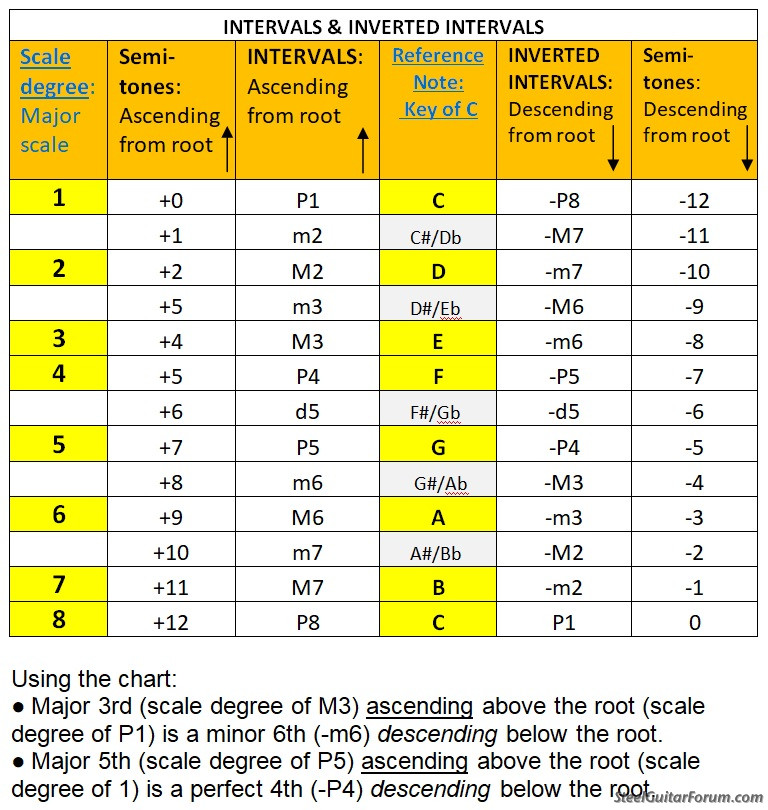

The common practice I have seen in all of the music theory books I’ve read is to count intervals ascending up from the root note.

For example, in the key of C, the E is a major third (M3) interval above the root note C.

• When my bandmates discuss singing or playing an E below C (in the key of C), they usually say “Sing/play the E below the root.”, or “Sing/play the third an octave below.”

This keeps it simple and everyone knows exactly what note to sing or play.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------.

OTOH, I have seen people talking on the Web about “a sixth harmony” when they are actually referring to singing/playing an A below C (in the key of C).

• This is confusing because it does not follow the standard terminology, in which “harmonizing with a sixth” would be playing an A above the C.

• It is also incorrect, as can be seen in the Inverted Intervals table below.

As you can see in the table above, an A above C is a major sixth (M6) interval above the root, but an A below C is a minor third (m3) interval below the root!

- Dave

Last edited by Dave Magram on 9 Jul 2024 7:29 pm; edited 2 times in total |

|

|

|

Tucker Jackson

From:

Portland, Oregon, USA

|

Posted 9 Jul 2024 8:21 am

Posted 9 Jul 2024 8:21 am |

|

I agree with Dave that for a lot of musicians, it's easier for them to understand 'play scale-tone 6, but an octave down' versus 'play a minor third below the root.' But either one works.

That's a cool chart you posted, Dave.

Here's an easy way to know all that stuff, with two rules.

Assume you play a harmony note that's higher than the root. You probably know the interval because we're used to thinking of them when they are above the root. But then we switch that note down an octave. What is the interval (distance) from the root note now?

1) Intervals above the root, and below the root add to 9.

2) Intervals that are major above the root swap and become minor when played down an octave.

And vice versa: what is minor above... toggles to become major when it is moved below the root.

Example: If you play C as the root note, then harmonize with an A note above that, that's scale-tone 6. That's a 6th interval.

If you move that 6th tone down an octave, what is the interval called now that it's below the root?

Per rule #1, the old and new intervals have to add to 9, so you know it's a 3rd of some kind (6+3=9).

And per rule #2, it will swap and become a minor interval, since the 6th interval was a major (for simplicity's sake, we usually just say '6th' but it's technically a 'Major 6th.' Intervals are assumed to be major by default, unless they're specified as something else, like minor).

Bottom line, that 6th swapped and became a minor 3rd when moved down an octave. Easy. And a Major 3rd when moved down would become a minor 6th, and so forth.

Two Caveats:

* It's only majors and minors that swap. Intervals that are Perfect ('Perfect 4ths' and 'Perfect 5ths'-- as 4ths and 5ths are technically called in music theory) remain perfect. But most everything else swaps when moved.

* The diminished 5th (or "flat-5" or tri-tone) is a one-off special case since it sits exactly at the halfway point in the middle of any octave. Therefore, it's equidistant from the root regardless of whether it appears above or below it, and it doesn't add to 9 like all the other intervals and nothing swaps. When moved down, it remains unchanged; it's still a diminished 5th (d5).

+++

It's maybe consuing that two intervals add to 9 if we're talking about the same harmony note that's an octave apart. Shouldn't they add to 8?

The reason they add to 9 is because that octave is being measured in two segments (from the root up, and then again, from the root down). And each segment includes the root note itself (due to the goofy way intervals are measured) -- so it's being double counted when you add the two segments together.

Last edited by Tucker Jackson on 9 Jul 2024 11:12 am; edited 1 time in total |

|

|

|

Peter Krebs

From:

Portland, Oregon, USA

|

Posted 9 Jul 2024 11:04 am

Posted 9 Jul 2024 11:04 am |

|

Thanks for your help! I feel like I’m still missing an essential piece of the puzzle, though.

Here’s my understanding;

Take four notes of a C6 tuning with the 5th on top. The notes would be: GECA, top down.

I recognize the interval pattern as m3rd, M3rd, m3rd, stacked.

If I play a straight-bar arpeggio on the top 3 notes (G, E, C), but harmonize each of these 3 notes with the string immediately below it, I get G/E, E/C and C/A (not slash chords, but just showing the notes I’m playing), I now see the stacked intervals as 6th, b6th, 6th below the “melody” note.

So far, so good.

This is where I’m stuck/confused. Am I just harmonizing my melody using 6ths now instead of 3rds? Does it sound good b/c my “melody note” is a 3rd/b3rd above above the 6th and the interval makes sense to my ears, even though I’m not harmonizing above?

Thanks for helping me unravel this. Pete. |

|

|

|

Tucker Jackson

From:

Portland, Oregon, USA

|

Posted 9 Jul 2024 12:19 pm

Posted 9 Jul 2024 12:19 pm |

|

| Peter Krebs wrote: |

If I play a straight-bar arpeggio on the top 3 notes (G, E, C), but harmonize each of these 3 notes with the string immediately below it, I get G/E, E/C and C/A (not slash chords, but just showing the notes I’m playing), I now see the stacked intervals as 6th, b6th, 6th below the “melody” note.

|

So, E and the C below it, for example, is still a major 3rd.

I think there's some confusion between the concepts of 'harmony over... or under?' versus which OCTAVE the harmony notes are in. In your example, those harmony notes would have to move up one octave to be higher in pitch than the root to become 6ths.

It's helpful to remember that interval is just distance.

Take your C and E strings. The distance between them is a major third. And it's a M3rd regardless of which one you call the melody and which one you call the harmony. If the lower string is the melody, the harmony is a 3rd above. But if the higher string becomes the melody, the lower string is still a 3rd, but it's now a 3rd below its root.

To make that lower C harmony note a 6th, with E as the melody, you would have to hit the C that's ABOVE it in pitch. This is the kind of conversion or octave move discussed in my prior post where old and new intervals add to 9 and all that -- and that E note would end up being a minor 6th when moved up an octave.

But you're not doing an octave move of a harmony note, just staying on the same two strings and declaring a different one is now the harmony. Different situation. The way your guitar is tuned, that C note appears below the E in pitch, so it remains fixed at all times as a 3rd interval. The distance between those two piches can't change with a straight bar.

So, long way around to say yes, those strings sound good together because they are the familar 3rds. Sometimes the harmony is 3rd above the root, sometimes a 3rd below the root.  |

|

|

|

Peter Krebs

From:

Portland, Oregon, USA

|

Posted 9 Jul 2024 2:12 pm

Posted 9 Jul 2024 2:12 pm |

|

Got it - OK, that makes sense. I was confused b/c when I think of the harmony note that’s the 3rd of, say, ‘C’, my brain says that note should specifically be the note ‘E’ (if it’s major). If it’s not an ‘E’, than you’re not harmonizing your melody note with the diatonic 3rd of that note, but another scale tone.

So… it’s not the specific note so much as the distance of the interval (either above/below). If I was to harmonize the scale of ‘C’ I could place that major or minor 3rd interval above or below each scale tone and they would be functional the same though the actual notes of the 3rd would be different? |

|

|

|

Tucker Jackson

From:

Portland, Oregon, USA

|

Posted 9 Jul 2024 3:46 pm

Posted 9 Jul 2024 3:46 pm |

|

| Peter Krebs wrote: |

| If I was to harmonize the scale of ‘C’ I could place that major or minor 3rd interval above or below each scale tone and they would be functional the same though the actual notes of the 3rd would be different? |

Unfortunately, they are not functionally the same thing. Sorry, I think I led you astray with the idea that a Major 3rd on two strings will always sound good because it always sounds the same, regardless of the context. That's actually not true. Context really matters as to when you can use the "3rd below." It's way different than when you use "3rd above" harmony.

And you had it right when you said, "when I think of the harmony note that’s the 3rd of, say, ‘C’, my brain says that note should specifically be the note ‘E’ (if it’s major). If it’s not an ‘E’, than you’re not harmonizing your melody note with the diatonic 3rd of that note, but another scale tone."

That's it. And a 3rd interval below isn't a valid example of "another scale tone" that works, at least to start off the scale. Sorry to imply that it would.

Let's say you're playing the first note of a C harmonized scale. If you play the E as harmony, the one that's above the C, that's a M3rd and that works. But if you play the note that's a M3rd below C it's a G# -- which you don't have on your tuning which is fine since it doesn't work here anyway. You do have a m3rd A note, and that works a lot better, but it introduces a scale-tone 6. Probably not what you're looking for with the first step of a straight C harmonized scale -- but totally useable in another setting in this key.

Though it didn't work here, a "M3rd below" harmony isn't useless. That G# below the C would sound horrible here, but would work just fine as, say, step 3 of an Ab scale. And slid up, in steps 6 and 7 of that scale. Context matters. In any major scale a harmony a "M3rd below" is the thing in positions 3, 6 and 7 as you walk up the scale.

If you're thinking about harmony notes below the root, it might be helpful to take that lower note and mentally cast it up an octave, then see what it is in the more familiar setting. A 3rd, 5th, 6th or 7th might be what you're looking for. If it works in that octave, it will work one octave down. You can then cast it back down and call it whatever you prefer... either, a 'M3rd, down an octave' or a 'm6th below the root.' |

|

|

|

Dave Magram

From:

San Jose, California, USA

|

Posted 9 Jul 2024 7:26 pm

Posted 9 Jul 2024 7:26 pm |

|

| Peter Krebs wrote: |

Thanks for your help! I feel like I’m still missing an essential piece of the puzzle, though.

Here’s my understanding;

Take four notes of a C6 tuning with the 5th on top. The notes would be: GECA, top down. |

Peter,

Are you open to an easy suggestion that would instantly eliminate a lot of confusion?

● When describing the tuning of string instruments, the common practice is to list the notes ascending from low to high (not top down).

● This means that the top four strings of your C6 tuning would be listed like this: "A,C,E,G" (bottom up).

● Now your tuning can be described as a 1-3-5 major triad with a 6th tone below the root, and every musician worth their salt will know instantly what you are talking about--because no matter how you invert it, it is still a C6 chord!

I am a big believer of the KISS principle: Keep It Simply Simple.

- Dave |

|

|

|

Mike Neer

From:

NJ

|

Posted 10 Jul 2024 3:32 am

Posted 10 Jul 2024 3:32 am |

|

Peter, inverted 3rds are 6ths. So a minor 3rd inverted would be a major 6th and a major 3rd a minor 6th.

Inverted 5ths are 4ths, etc.

Forgive me if anyone else already posted this.

_________________

Links to streaming music, websites, YouTube: Links |

|

|

|

D Schubert

From:

Columbia, MO, USA

|

Posted 10 Jul 2024 7:00 am

Posted 10 Jul 2024 7:00 am |

|

It's a lot like the way that male/female duos sing on the chorus. Think Porter and Dolly, George and Tammy...

_________________

GFI Expo S-10PE, Sho-Bud 6139, Fender 2x8 Stringmaster, Supro consoles, Dobro. And more. |

|

|

|